Wee Lee first got in touch with me an hour after I posted an online appeal for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people in Singapore to contribute their personal stories. We decided to meet over drinks in Holland Village; I was half-expecting him to share his coming out story, and was not ready for some of the things he was about to tell me.

Wee Lee first got in touch with me an hour after I posted an online appeal for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people in Singapore to contribute their personal stories. We decided to meet over drinks in Holland Village; I was half-expecting him to share his coming out story, and was not ready for some of the things he was about to tell me.

As an average-looking guy with an athletic build and broad smile, he didn’t look too different from other young men. Yet what I heard from him that night was to change my understanding of human endurance. You see, Wee Lee is a survivor of violence inflicted upon him by his gay partner.

As a gay man and a social worker, I thought I had seen it all. Before this, my experience of family violence had been the kind between straight couples, or when someone vulnerable, such as a child, or an elderly or disabled person, is being mistreated by a family member. I had heard from someone else about a friend who was being beaten up by her lesbian partner; I think they lived in the US. All these cases of domestic violence, although real and tragic, seemed somewhat remote from my own life.

As a gay man and a social worker, I thought I had seen it all. Before this, my experience of family violence had been the kind between straight couples, or when someone vulnerable, such as a child, or an elderly or disabled person, is being mistreated by a family member. I had heard from someone else about a friend who was being beaten up by her lesbian partner; I think they lived in the US. All these cases of domestic violence, although real and tragic, seemed somewhat remote from my own life.

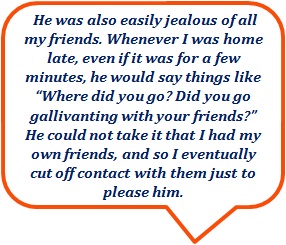

Still, just because we don’t hear or talk about something doesn’t make it non-existent. International research has shown that rates of violence in same-sex (gay and lesbian) relationships is very similar to rates of violence against women by their male partners – around 25% to 30%. This can only mean that same-sex partner violence happens right here in Singapore: to our neighbours, friends, colleagues and family members. Wee Lee was in a four-year relationship with his abusive partner Carl while they lived together in a flat near Ghim Moh.

What is partner violence?

What is partner violence?

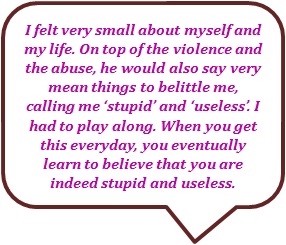

Partner violence is about power and control; it happens when one partner intentionally exerts that power through behaviours that seek to control the other. It can happen to anyone, regardless of their social class, educational level, profession, gender and sexual orientation.

It can take many forms: physical and sexual attacks, emotional and psychological abuse, even financial exploitation. For same-sex couples, there is the threat of outing someone’s sexual orientation to others, such as family members or work colleagues. In relationships where one partner is transgender, abuse can take the form of threatening to embarrass their gender identity in the presence of others.

What prevents people from seeking help?

Yet there are probably as many barriers to seeking help as there are lesbians and gay men. Bryan Choong is centre manager of Oogachaga Counselling and Support, a non-profit agency that provides a range of professional counselling and support services for the LGBT community. He offers some common reasons why so few LGBT people in Singapore are seeking help for partner violence.

“In the gay community, there are many who do not believe that someone will be abused or hurt by a same-sex partner. Many think that it is always easier to walk out or fight back.”

There are victims who are afraid that by revealing their abusive experience, they are also exposing their sexual orientation and same-sex relationship to others. This has much to do with a general lack of awareness about partner violence in the LGBT community, which may also explain why many victims do not see the need to seek help, are unaware of where to go for support, or feel embarrassed to reach out.

There are victims who are afraid that by revealing their abusive experience, they are also exposing their sexual orientation and same-sex relationship to others. This has much to do with a general lack of awareness about partner violence in the LGBT community, which may also explain why many victims do not see the need to seek help, are unaware of where to go for support, or feel embarrassed to reach out.

It is a common misconception that it needs to be physical for it to be considered as abuse. “Sometimes, even the victims get confused with whether abuse is an acceptable part of their relationship, or they are just being too sensitive. For example, in cases of sexual violence, the abused partner may think it is just part of role-playing in bed,” explains Choong.

Serene Tan, a senior social worker with Care Corner Project START (Stop Abusive Relationships Together) which works with victims and perpetrators of family violence, adds on to the list of obstacles facing LGBT victims.

“The LGBT community is relatively small, and couples usually have a common circle of close friends. They may feel that even if they are experiencing violence from their partners, their friends would not believe them or would not take their side. Hence they would choose to keep quiet. Some of them may also be isolated and do not have a good support network.”

“The LGBT community is relatively small, and couples usually have a common circle of close friends. They may feel that even if they are experiencing violence from their partners, their friends would not believe them or would not take their side. Hence they would choose to keep quiet. Some of them may also be isolated and do not have a good support network.”

Unfortunately, the current legal system in Singapore is also not helping. Section 377A of the Penal Code continues to criminalise consensual sex between adult men, and the same level of protection for married heterosexual couples is not available to committed same-sex couples. While a married man or woman can apply for a personal protection order from the Family Court against their abusive spouse or ex-spouse, a gay man or lesbian is not able to do the same. Instead, they can only report the offence to the police or take out a private summons against the abusive partner through the Subordinate Courts, which is a tedious process and offers a lower level of protection.

All these reasons serve as very real barriers that prevent a victim of LGBT violence from seeking help. Sadly, as part of Oogachaga’s ongoing outreach services through the Internet, Choong has made observations about responses from within the LGBT community.

All these reasons serve as very real barriers that prevent a victim of LGBT violence from seeking help. Sadly, as part of Oogachaga’s ongoing outreach services through the Internet, Choong has made observations about responses from within the LGBT community.

“The understanding of this issue is so low… it is common to read in local forums that one should not be too ‘drama’ by claiming their partner is violent; or maybe one must have done something ‘wrong’ to deserve a violent treatment.”

Tan, whose professional experience includes working with same-sex as well as heterosexual couples in abusive relationships, adds,

“No one starts out with the intention to hurt their partner. However, they may lack the appropriate coping skills or effective communication skills to convey their needs to their partner, resulting in them using violence to obtain power and exert control.”

So how can WE help?

According to Tan, it is important that concerned family members and friends adopt different approaches toward helping victims and perpetrators.

For the abused victim:

- Assure them it is not their fault that their partner used violence on them

- Offer a listening ear

- Encourage them to talk to someone, such as a professional, to help with their issues

- Check in on them with regard to their safety

- Invite them to call you in case of an emergency

- Offer to call the police for help when there is danger

For the abusive perpetrator:

- Let them know that they should seek professional help with their issues

- Encourage them to work on using other ways of resolving their issues

- Provide a listening ear, but do not condone their abusive actions, or agree with what they are doing as being right.

In addition to Oogachaga’s hotline, email and counselling services for the LGBT community, those affected by partner violence can also contact Care Corner Family Service Centre (Queenstown) where Project START is based. However, according to its website, I noted that one of their key missions is “To base all activities on Christian values”. This statement may worry many in the LGBT community, since the traditional stand adopted by Christianity is to condemn homosexuality and transgenderism as “unnatural” and an “abomination”.

When I asked about this, Tan clarifies by saying,

“Although Care Corner is a Christian-based organization, we serve all clients in the community who are in need, regardless of their race, religion, socio-economic status or educational level, and provide the same level of service to people from all walks of life. We also follow the professional code of ethics and believe in seeing each person with their individual worth, regardless of their worldview, sexual orientation and the choices that they make. We also ensure that confidentiality is maintained, unless harm has been done to self or others.”

Additionally, Tan explains that at Project START, working with someone affected by partner violence means focussing on developing a safety plan together, so as to keep them safe, regardless of whether they wish to continue in the relationship. If a client chooses to stay in the relationship, they will invite the abusive partner to attend counselling sessions to work on using more effective ways of coping or communicating with one another.

To the wider LGBT community, Choong has this message:

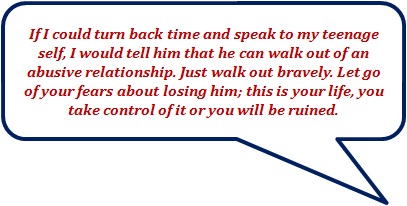

“Under no circumstances should anyone have any reason to be emotionally, verbally, physically or sexually abusive to another person, even if they are in a relationship. If you are a victim, do not be afraid of seeking help or talking to someone who can support you. If you are not in a violent relationship, arm yourself with knowledge on how and when to assist a friend who may need your help. “

We all know love can sometimes hurt, but it shouldn’t be in this way. LGBT partner violence is very real and occurring in Singapore. We need to keep talking about it so that it does not remain invisible.

* * *

What happened to Wee Lee?

Towards the end of my hour-long interview with Wee Lee, during which he also showed me the scar where he was stabbed by his partner’s knife, I was told that his relationship, and his ordeal, finally ended after four-and-a-half years.

____________________________________________________________